Civil Constitution Of The Clergy

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy was passed past the National Associates in 1790. Information technology attempted to reorganise and regulate the Catholic church in France, bringing information technology into line with national values. The Civil Constitution became one of the new regime's almost divisive policies and, over time, an important turning point of the French Revolution.

Summary

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy sought to realign French Catholicism with the interests of the state, making information technology subject to national law. It as well attempted to eliminate corruption and abuses within the Church.

The Civil Constitution reduced the number of bishops and archbishops, made the clergy paid employees of the government and required all members of the clergy to swear an adjuration of loyalty to the nation.

Controversial from the kickoff, the Civil Constitution became i of the new regime's most controversial, confusing and divisive measures. It created more dissent and fuelled more opposition than any other revolutionary policy.

According to 19th-century historian Thomas Carlyle, the Ceremonious Constitution was "simply an understanding to disagree. It divided France from end to end with a new dissever, infinitely complicating all the other splits."

Revolution and religion

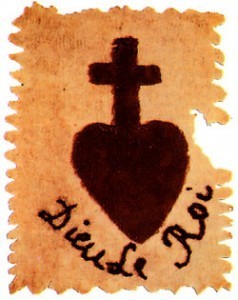

The relationship between the revolution and the Cosmic church building was always problematic. The late 18th century had thrummed with criticism of organised religion and the Starting time Manor.

Writers like Voltaire condemned the church's excessive wealth and state ownership, its undue political influence, its endemic abuse and venality, and the debauched carry of some clergymen.

Several critics of the Catholic church were clergymen themselves, men similar Emmanuel Sieyes, Charles de Talleyrand and Henri Grégoire. At the Estates-General in 1789, many of these dissenting clerics crossed the flooring, sided with the 3rd Estate and joined the National Assembly.

Criticisms of clerical behaviour and calls for church reform did not always mean opposition to the church, however, nor did it suggest disbelief or a lack of faith. The vast majority of revolutionaries retained Christian religious beliefs and maintained support for the church. What they wanted was a church free of corruption, free of foreign control and answerable to both the nation and its people.

Focus on the Church building

Activity against the church began in the start weeks of the National Constituent Assembly. The August 4th session that dismantled seigneurialism in France also stripped the church building of its rights as a feudal landowner.

Presently after, the Assembly formed an Ecclesiastical Committee, comprised of revolutionary priests and lawyers, to provide communication on religious and clerical policies.

By late 1789, there was a consensus in the Associates that the church should surrender much of its wealth, to aid alleviate the national debt. In return, the national government would presume responsibility for clerical salaries and save the church of its responsibilities for teaching and poor relief.

In September 1789, the National Constituent Assembly abolished the taxation privileges of the Beginning and Second Estates. Two months afterward, the Assembly nationalised all church-owned lands. Property seized from the church building was accounted biens nationaux or 'national goods'; the auctioning of this property began in late 1790. Acquirement from the auction of church building lands was used to underwrite newly issued paper bonds called assignats. In Feb 1790, the Assembly ruled that monastic vows were no longer legally binding.

Dioceses reduced

The following month, the Assembly reduced the number of dioceses from 130 to 83, adjustment them with the newly formeddépartements. On April 14th 1790, deputies voted to abolish the tithe, effective from Jan 1st the following yr.

These reforms were followed by the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, passed by the National Elective Assembly on July 12th 1790.

This was the almost radical modify of the revolution to that bespeak. The Assembly reorganised and standardised parish sizes on the basis of both geography and population. The salaries of parish priests were to exist fixed by and paid for by the state. These salaries ranged from 1,200 to vi,000 livres per year, depending on the location and the nature of clerical duties.

For most parish priests, this represented an increase in their pre-1789 salaries. The salaries of bishops, in contrast, were significantly reduced to effectually 12,000 livres per annum. Bishops were as well required to live permanently inside their diocese (in pre-revolutionary France there had been many absentee bishops and archbishops, men who preferred the liveliness of Paris or other locations to their own diocese).

Bishops and priests would also be elected past a local or regional assembly, not appointed by the Vatican. More than controversially, the electors in clerical elections did non have to be Catholic.

The clerical adjuration

If these changes were not divisive enough, the Civil Constitution of the Clergy as well required bishops to swear an oath of loyalty.

A clerical oath was non in itself a radical departure from existing customs. Ever since the reign of Louis XIV, newly consecrated bishops were required to nourish services at Versailles and swear an oath of loyalty to the male monarch. Nether the terms of the Civil Constitution, each bishop was required to swear "loyalty to the nation, the law and the king" and "to support with all his power the constitution decreed by the National [Elective] Assembly".

In November 1790, the Associates issued a decree that extended this compulsory oath to all members of the clergy. Parish priests, abbés, curates, monks and nuns were also required to swear loyalty to the nation. If lower clerics were to be paid by the land, information technology was argued, then information technology was reasonable that they swear an oath of loyalty to the state, in a similar fashion to the oaths taken by public officials.

Juring and non-juring priests

Forcing clerics to swear loyalty to the nation created a crunch of censor. A clergyman's oath to the state, it was argued, might conflict with his loyalty to God and his obedience to the Pope.

Within the clergy, opposition to the oath was stiff. In Oct 1790, several clerical deputies in the National Elective Associates alleged they would boycott and defy the Assembly's policies on religion until they had received instructions from the Pope. There should be no reforms to the church building, they argued, that were not based on consultation with the church building.

The majority of higher clergymen afterward refused to swear the adjuration. The ordinary clergy, notwithstanding, were more divided. When the process began in January 1791, the oath was taken by effectually 60 per cent of parish priests. Those who submitted and took the oath became known equally 'juring priests' or the 'constitutional clergy'. Those who refused the oath were dubbed 'non-juring' or 'refractory priests'. These dissenting priests were afterward removed from their posts, past order of the Associates.

The Vatican responds

The state of affairs evolved farther on March 10th 1791 when the Vatican finally responded to the changes being imposed upon the church in France.

As a former aristocrat, Pope Pius Vi was naturally hostile to the French Revolution. In airtight-door meetings with his cardinals, Pius condemned the revolution in strong terms, particularly the Baronial 4th decrees (which annulled the church'south feudal rights) and the Proclamation of the Rights of Man and Denizen (which he considered heretical).

Publicly, nonetheless, the Pope said zilch until Apr 13th. On this twenty-four hour period, Pius released "Charitas", an encyclical responding to "the war against the Catholic religion started past the revolutionary thinkers who form a majority in the National Assembly of France".

In this encyclical, the Pope condemned the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and claimed that Louis Sixteen had only signed it under duress. Pius as well declared that constitutional bishops and priests would be suspended from function unless they renounced the adjuration.

The clergy takes sides

Back in French republic, the pope's open condemnation of the Ceremonious Constitution hardened opposition among the local clergy. Many clerics who had pondered taking the oath now refused to do and then. Some who had already taken the oath renounced it, in line with the pope's orders.

By the spring of 1791, the Catholic church in France was divided between clerics willing to swear loyalty to the nation and those who remained loyal to Rome.

Beyond the nation, hundreds of non-juring priests defied the national regime past remaining in their parishes, fulfilling their duties and jubilant mass. These refractory priests often enjoyed the support of their parishioners, who objected to a secular government interfering in spiritual matters. Non-juring prelates and parish priests were particularly mutual in Flanders, Alsace, Brittany, the Vendée and the city of Lyon.

Unwilling and unable to force the consequence, the National Constituent Assembly compromised and issued a 'tolerance decree' on May 7th.

The French Church building in schism

By this signal, revolutionary French republic had two dissever Catholic churches. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy attempted to align the church building with the revolution and to create a national religion. Instead, it instigated a schism within the French church and created a new source of counter-revolutionary sentiment.

The Civil Constitution alienated thousands of deeply religious French citizens. It pressured the Pope into condemning the revolution. Information technology also gave reactionaries fresh grounds to attack the National Constituent Associates.

Louis XVI, a devoutly religious man, was as well deeply affected by the Civil Constitution. The king had tolerated the revolution's political reforms and the erosion of his own ability – merely he could not endorse attacks on the church. In Louis' mind, he would not jeopardise his immortal soul past accepting communion from a constitutional priest.

The Assembly'due south attempt to purge the Catholic church and force its loyalty to the nation backfired, fuelling opposition and making the new regime even more difficult to govern.

A historian's view:

"With the Ceremonious Constitution of the Clergy, the Revolution and the Church were set on a collision form. Religion and revolution, in the words of the historian Jules Michelet, became increasingly incompatible, and matters religious became implicitly political. As a outcome of the debacle over the oath, the Cosmic church came to be associated with counter-revolution, reaction and France's pre-revolutionary by, which the Revolution wished to eradicate."

Caroline C. Ford

ane. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy was an attempt to reform and regulate the Cosmic church in France. It was passed by the National Constituent Assembly on July 12th 1790.

2. It followed other measures taken by the Assembly against the church, including the abolition of feudal dues, the confiscation and sale of church lands and the suppression of tithes.

3. The Ceremonious Constitution allowed the state to presume control of some aspects of religion, including funding of clerical salaries and the responsibility for education and charitable works.

4. It also required bishops and then all clergy to swear an oath of loyalty to the country, to be taken in January 1791. Most bishops did non take this oath, though around 60 per cent of lower clergy did.

5. In April 1791 Pope Pius VI issued an encyclical condemning the Civil Constitution and threatening to suspend all clergy who took the oath. The Ceremonious Constitution became a meaning cause of division and disruption in the new society.

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy (1790)

A Paris newspaper on the Civil Constitution of the Clergy (1790)

The National Constituent Assembly's prescript on the clerical oath (1790)

A non-juring priest explains his decision not to accept the Assembly's clerical oath (1791)

"Charitas": Pope Pius 6 responds to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy (1791)

The Legislative Assembly threatens to deport not-juring clergy (1792)

Citation information

Championship: "The Civil Constitution of the Clergy"

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/civil-constitution-of-the-clergy/

Date published: September 2, 2020

Date accessed: Oct 12, 2022

Copyright: The content on this folio may not exist republished without our limited permission. For more than information on usage, delight refer to our Terms of Utilise.

Civil Constitution Of The Clergy,

Source: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/civil-constitution-of-the-clergy/

Posted by: ratliffpeammeak.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Civil Constitution Of The Clergy"

Post a Comment